MEF2C Haploinsufficiency Syndrome Volare Study Webinar

Date: November 1, 2025

Host: Weill Cornell Medicine / Children’s Hospital of New York

Co-Hosts: Rare Bird Foundation X MEF2C Foundation (UK) X MEF2C Foundation (GER) X MEF2C Foundation (AUS)

10:00–10:02 |

Welcome & Introductions

Zach Grinspan: Alright, it is 10 o’clock right now, so why don’t we get started? You never want to punish people for being on time. It’s nice to see everybody. I’m Zach Grinspan. I am Director of Pediatric Epilepsy Research and Vice Chair of Health Data Science at Weill Cornell Medicine, and I’m the PI for the natural history study — the Volare study — for clinical-trial readiness for MEF2C haploinsufficiency syndrome.

It’s a real pleasure to be here. I’m grateful to all of you for joining the webinar today. I’ll give some updates, and there’ll be plenty of time for Q&A.

I’ve turned on captions for those in noisy places, and I’ve muted people as they’ve joined. Isra and James, I think you should be able to do that as well if there’s background noise. This is a standard Zoom — after the talk, please feel free to ask questions.

I’ve turned on the AI Companion so people can chat with context if they like, and I’m recording this as well so we’ll have a transcript to work with later.

Isra, before I start, anything you want to add?

Isra Bhatty: I’d just like to welcome everyone. I know it’s different hours of the day around the world, so thank you all for joining. I want to recognize my co-hosts: James from Rare Bird, as well as the MEF2C Foundation, Lorena, and Maria from the MEF2C Foundation in Germany; and Claire and the team at MEF2C Foundation Australia, who couldn’t join because it’s midnight there. They tuckered out a bit early. I’m sure they’ll have things to share afterward. And I want to say thank you to you, Zach, for taking time out of your schedule to do this for us.

Zach Grinspan: My pleasure. Thank you.

10:02–10:07 |

Opening Remarks & Major Updates

Zach Grinspan: Welcome, everyone, from Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City. Today I’ll talk about our natural history study — the Volare study — which is our natural-history project for clinical-trial readiness for MEF2C haploinsufficiency syndrome.

A big shout-out to the Rare Bird Foundation, which has funded this entire effort. Isra mentioned that multiple rare-disease advocacy groups are working together — and what we’ve seen across groups is that there are many instincts: to start foundations, to connect locally, to go national or international, to focus on research or clinical care.

But when the community comes together to fund a unified research study, the atmosphere and goodwill are incredible. The progress that parents, caregivers, and advocates make in these collaborations is truly remarkable — some of the most rewarding work I’ve ever done.

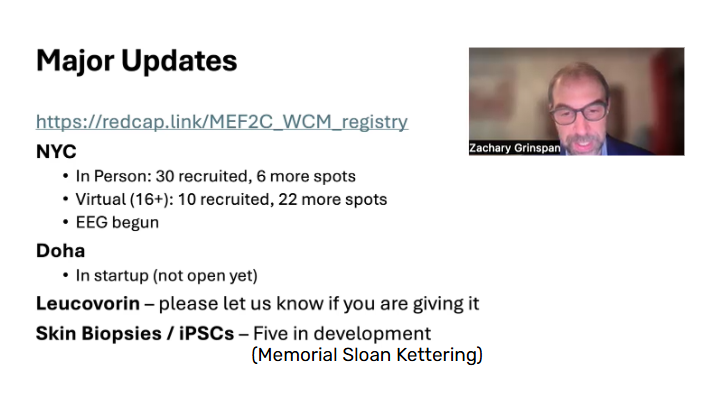

So, major updates before we get into details:

• The registry is still open — the link appears multiple times in these slides. If you’re not yet in it, please join.

• At Weill Cornell in New York, we’ve recruited about 30 participants; we have 6 more spots.

• For the virtual arm, we’ve recruited 10; we have 22 more available.

• The EEG component took a little longer to start than expected but is now up and running.

• A second site in Doha, Qatar, is in startup — not yet open but progressing — using the same protocol and shared data structure.

• There’s been national and international attention around leucovorin — a vitamin therapy used in some conditions involving folate deficiency in the brain. Literature suggests it’s rare, but we want to capture any experience families have.

• On the research side, we’ve begun collecting skin biopsies to generate fibroblasts and iPSCs. We now have five in culture. Our colleagues at Memorial Sloan Kettering — just across the street — are partnering with us. Those cells give us programmable models carrying each child’s MEF2C variant, providing key material for Dr. Chris Cowan’s therapeutic work at MUSC.

Enroll in the Volare Study:

https://redcap.link/MEF2C_WCM_registry

10:07–10:09 |

Team Introduction

Zach Grinspan: I want to highlight our team — it’s large and growing.

Physician researchers include myself; Dr. M. Elizabeth Ross, who directs our Center for Neurogenetics; Dr. Dara Jones in Physiatry; and Dr. Jennifer Cross in Developmental Pediatrics. Heidi Bender, PhD, neuropsychology, and her team are now contributing to developmental assessments. Ji-Sun Kim, genetic counselor, is helping manage coordination. EEG analytics are led by Dr. Sudin Shah and her postdoc, Ludvik Alkhoury. Our research staff — Millie, Natalie, and Natasha in my lab, and Isabelle in Dr. Shah’s lab — are amazing, and our biostatisticians Alan Wu and Will Simmons support data analysis. Natalie Wayland has been leading organizational logistics and doing an outstanding job.

10:09–10:13 |

Background & Study Approach

Zach Grinspan: Let’s talk about how this differs from what’s been done before.

Traditionally, when researchers studied a rare disorder, they built a registry, tried to see as many participants as possible, sometimes once, sometimes more. The purpose was disease characterization: what does the syndrome look like, what symptoms are common. The assessments were broad, the visits ad hoc, and data gaps were tolerated. The audience was other academics and clinicians.

In contrast, what we’re doing in the Volare study is designed for clinical-trial readiness. We’re thinking ahead to therapies and the regulatory audiences — the FDA, EMA, and others. Assessments are targeted and age-specific; visits occur at fixed intervals; missing data are minimized. The audience includes industry and regulators because we want to show that this disease is ready for therapeutic investment — we’re “de-risking” the space for development.

In MEF2C-related disorders, Dr. Cowan’s prior work (n=73) gave a strong foundation: half male, half female, mostly white non-Hispanic, ages nine months to thirty-eight years (mean eight). About 40% had point mutations or small INDELs, 55% large deletions, 5% uncertain. Developmental milestones were delayed — sitting achieved late but usually attained; rolling common; fewer children crawled or used pincer grasp; utensil use limited though some adults achieved it. Girls tended to do slightly better with communication and walking.

Seizures occurred in roughly 86%, starting mostly in infancy or early childhood; many required daily medication. Other frequent features: visual impairment, sleep disturbance, and a generally affectionate, sweet temperament — something we see consistently across the children in our clinic.

Chief of Child Neurology, Weill Cornell Medical Center (NY)

Principal Investigator, the Volare Study

10:13–10:19 |

Developmental Modeling & Clinical-trial Readiness

Zach Grinspan: I want to illustrate how we conceptualize development here. Picture chronological age on the x-axis and developmental age-equivalent on the y-axis. A neurotypical child progresses along the diagonal. Children with MEF2C reach a plateau — they continue growing but development slows relative to age.

Our hope with new therapies is not necessarily to normalize development but to raise that plateau — to shift the curve upward. We can model this mathematically using an exponential function with a single parameter, k, which represents the developmental plateau level. A simple model helps us run statistics, predict trajectories, and evaluate change once interventions begin.

We’ve applied similar methods in other DEEs such as STXBP1 (Simons Searchlight data, Wendy Chung’s team). Their dataset had ad hoc visits, but our fixed intervals and uniform assessments should yield more powerful modeling for MEF2C.

10:18–10:21 |

Study Design & Participation

Zach Grinspan: Here’s our study layout:

• Arm 1: In-person intensive visits, four over two years, ages 0–15.

• Arm 2: Virtual visits, two over two years, ages 16 and older.

• Arm 3: Online registry, open to all ages.

Sidra Medicine in Doha is coming online as our international partner.

We’re especially eager to recruit older individuals for the virtual arm.

Inclusion: confirmed MEF2C haploinsufficiency and a neurologic phenotype (developmental delay, epilepsy, or both).

We’re starting with English-language participants because several developmental tools require English comprehension, though bilingual families are fine if communication is comfortable.

We’ll broaden language inclusion once Doha is active.

Exclusions are primarily for conditions that would obscure interpretation — e.g., severe prematurity, large structural brain lesions, or unrelated syndromes.

10:21–10:24 |

Measures & Visit Structure

Zach Grinspan: Assessments cover development, communication, motor function, behavior, quality of life, sleep, hand use, and epilepsy.

Each domain has instruments — Vineland, Bayley, PDMS, GMFM-88, AIMS, ORCA, CFCS, ABC, CARS, PELHS QOL-2, QI-Disability, CSHQ, PSQ, MACS, seizure diaries, and EEG.

For in-person participants, we also collect blood and optional skin biopsies.

Travel reimbursement: up to $1,500 per trip within the US/Canada/Mexico; up to $2,500 internationally.

We’re fully 21 CFR Part 11 compliant so that FDA reviewers can audit data integrity. Enrollment is rolling.

In New York, clinic begins around 8 a.m. — exam, developmental testing, blood draw, optional skin biopsy — then we walk five blocks to Dr. Shah’s EEG lab for biomarker recordings.

Importantly, none of this is billed to insurance. Earlier we had some confusion with EEGs being charged; that’s fixed. Research visits are entirely covered by the study.

10:25–10:29 |

Preliminary Findings

Zach Grinspan: Preliminary genetics from 40 participants show a mix of frameshift, nonsense, missense, promoter, and splice variants, plus partial and whole-gene deletions. Five are now represented as cultured fibroblast lines proceeding to iPSCs at Memorial Sloan Kettering.

Developmental measures (Vineland, Bayley) show:

• Receptive and expressive language mostly below a one-year developmental equivalence.

• Gross motor skills improve slowly — many achieve independent walking by age 8–9.

• Fine motor control remains limited; pincer grasp and utensil use are often absent or delayed.

These are early, cross-sectional results. As longitudinal data accrue, we’ll fit growth curves and quantify individual trajectories.

10:29–10:31 |

Closing Summary Before Q&A

Zach Grinspan: To recap:

The registry remains open — please enroll if you haven’t. We have six open in-person slots and many more for ages sixteen and up in the virtual arm.

The EEG component is now part of all return visits.

If you’re using leucovorin, let us know.

Skin biopsies are optional but critical for the iPSC library.

This is a collaborative effort with Rare Bird and advocacy groups worldwide — a shared achievement.

10:31–10:53 |

Q&A Session

Audience: My daughter started leucovorin in June.

Zach Grinspan: Thank you. Please let us know at your visit so we can record that. There are two biological mechanisms for folate deficiency in the brain: antibodies to the receptor and mutations in the receptor itself. True cerebral-folate deficiency is thought to be rare, but a few clinicians believe it’s under-recognized. There’s mixed experience — some report benefit, most see limited effect. It’s generally benign since it’s a vitamin, but you do need a prescription. We’re not testing it formally; we’re documenting experiences while focusing our main statistical power on gene-targeted therapeutics.

Audience: Could we do an overnight EEG at your site?

Zach Grinspan: Yes, that would be a clinical EEG through insurance. I’d put on my “doctor hat” for that visit. For families without US insurance, hospital charges can be extreme — we once saw a quote of $300,000 for an inpatient study — so we handle that carefully. Our research EEGs are brief, non-billed sessions for biomarkers only.

Audience: We had a local EEG — would that be useful?

Zach Grinspan: Absolutely. Please get a copy on disc and bring or send it. Clinical EEGs are valuable, and our research partner, Dr. Shah, performs additional paradigms — “beeps and boops” auditory tasks that evoke specific EEG responses to novelty and speech comprehension. Those help us explore biomarkers, but all EEG data are welcome.

Audience: Could you post the registry link?

Zach Grinspan: Sure — it’s https://redcap.link/MEF2C_WCM_registry, also on the Rare Bird website. Registering doesn’t commit you to participation; it’s essentially a census so we understand where families are globally. You can opt out of re-contact. If you opt in, we may reach out about study eligibility depending on age.

Audience: What’s the expectation for when Dr. Cowan’s therapeutic will be available?

Zach Grinspan: We’re waiting for readiness from his team. Once a therapy is proven safe, things can move quickly — in one prior case, once funding and manufacturing aligned, treatment reached the patient within nine months. So timelines depend on safety confirmation and logistics, but the path can be swift once ready.

Audience: What about broader 5q14 deletions including multiple genes?

Zach Grinspan: Excellent question. Early trials often begin with those most likely to respond — typically single-gene haploinsufficiency. In the 5q14 region, MEF2C appears to be the primary driver of the phenotype, so therapies targeting MEF2C may still help those with larger deletions. Gene-editing approaches might one day address complex deletions, but that’s likely years away.

Audience: Is cerebrospinal fluid being collected?

Zach Grinspan: Not in this phase. CSF collection requires sedation and raises ethical and logistical challenges for repeated procedures in children. Advocates from other DEE communities indicated families would be reluctant. If we move to therapeutic delivery via intrathecal routes (AAV or ASO), we’ll collect CSF then for analysis, but not during observational visits.

Audience: How do donations work? Are there tax benefits?

Donate to the Volare Study:

Paypal: https://www.paypal.com/donate/?hosted_button_id=2EFDPAT5QXTU8

Go Fund Me: https://www.gofundme.com/f/global-steps-for-mchs

James Kelly: Donations are most efficient through your home foundation — Rare Bird for US donors, the UK, EU, and Australian partner foundations abroad. That maximizes tax relief (for example, Gift Aid in the UK adds about 25%). Everything ultimately supports the same research and is transferred without indirect costs.

James Kelly: Exactly. Different countries have mechanisms, but it all funnels to the same program. Another 6 months should yield the second-visit dataset; we can host another webinar then to show trends.

Zach Grinspan: Thank you, James. Truly, advocacy has made this happen at record speed. Two years ago this was an idea; now we have more than 20 enrolled participants, longitudinal visits underway, and data being analyzed. None of that happens without persistent advocates like you and Isra keeping us on track.

Isra Bhatty: Thank you, Zach. We’re thrilled with the progress. I think everyone here appreciates how much effort you and your team are investing.

Audience: Is there any estimate of when gene therapy might begin?

Zach Grinspan: Not yet. Dr. Cowan’s lab is refining the construct; once it’s ready and safe, we can move quickly. Safety always comes first, but we’re optimistic.

Audience: Could families with larger deletions still benefit if MEF2C therapy works?

Zach Grinspan: Possibly yes. MEF2C likely contributes the most to the phenotype, so increasing its expression could improve outcomes even when other genes are involved. We’ll learn more as therapies advance.

10:53–10:54 |

Closing Remarks

Isra Bhatty: Thank you, Zach, for spending your morning with us. I think everyone here would agree we’re so appreciative of you and your team. The presentation was wonderful, and we’re excited for the next phase. As therapeutic development accelerates, your data will be critical for FDA and global regulatory engagement.

Please feel free to reach out to me, to James, or anyone else on our team with questions. And thank you to everyone who joined today.

Zach Grinspan: Thank you all. Enjoy the day, and be well.

Audience: Thank you.